2024

|

In writing: Truth does not necessarily have to agree with facts….

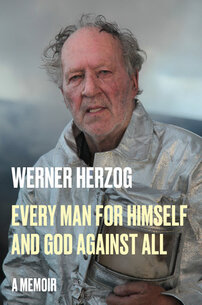

“The French novelist André Gide once wrote: “I alter facts in such a way that they resemble the truth more than reality.” Shakespeare observed similarly: “The most truthful poetry is the most feigning.” That busied me for a long time. The simplest instance is Michelangelo’s Pietà in St. Peter’s in Rome. The face of Jesus, just taken down from the cross, is the face of a thirty-three-year old man, but the face of his mother is the face of a seventeen-year-old girl. Was Michelangelo lying to us? Did he wish to deceive us? Disseminate fake news? As an artist, he behaved perfectly straightforwardly by showing us the deepest truth of the true people. What the truth is is something none of us knows anyway, not even the philosophers or mathematicians or the people in Rome. I never see the truth as a fixed star on the horizon but always as an activity, a search, an approximation.” Film director and opera director Werner Herzog, Every man for Himself and God Against All – A Memoir, Penguin Press/Random House, New York, 2023 (p. 285-6) March 1 |

|

On Writing: A Challenge to the Reader

drabble

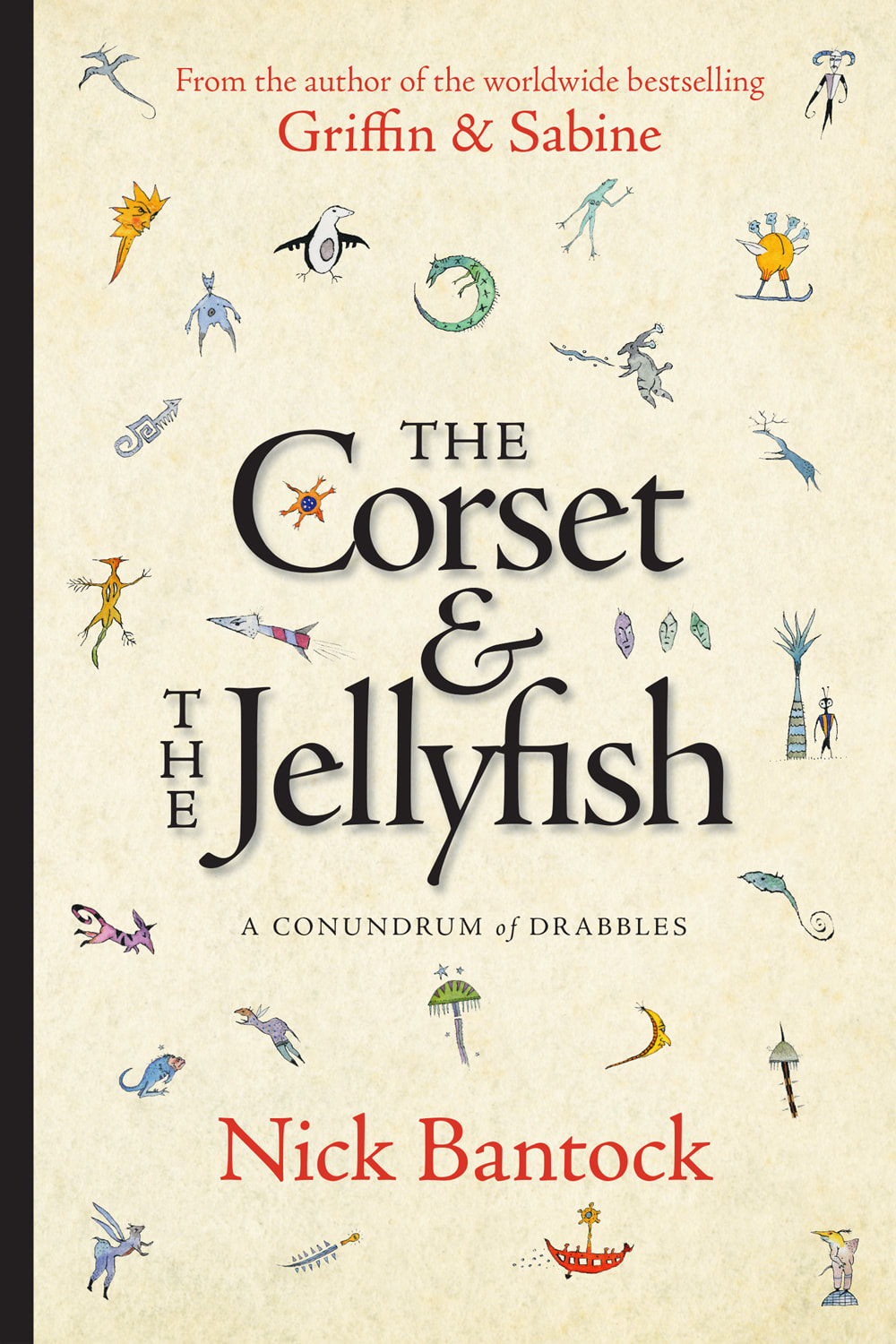

In The Corset and the Jellyfish – A Conundrum of Drabbles, celebrated author and illustrator Nick Bantock assembles 100 “drabbles” of no more than a hundred words, each drabble is accompanied by an enigmatic icon. Bantock suggests there is, perhaps, a missing drabble and that the reader “is being asked to create an additional one-hundred-word story by selecting a single word … from each of the tales.” Bantock’s book also contains other forms of illustration – as in a demonstration of how to write an effective opening line:

Nick Bantock, The Corset and the Jellyfish – A Conundrum of Drabbles, Tachyon Publications, 2023 February 19 |

|

The French translator, Mireille Gansel, is the daughter of Jewish refugees who escaped the Nazis when they moved to France. Hungarian, Yiddish, and German were the languages spoken at home. Born in 1947, she is one of the major figures in literary translation. In her book, Translation as Transhumance (English translation by Ros Schwartz), she explains the evening when, as a young child, her father read a letter in Hungarian and tripped up on a word when translating it into French for her. It was the moment she discovered that working with language would become her life-long vocation:

One evening is particular stands out in my memory, when for the first time I experienced viscerally, without yet realizing its significance, what ‘translation’ would come to mean for me. It all happened with the utmost simplicity, as is often the case when something is important. He initially translated a word used by his brother or one of his sisters as ‘beloved,’ stumbled over the next word and repeated this -- actually rather ordinary -- adjective once, stumbled again, and then repeated it a second time. That triggered something in me. I dared to interrupt him. I asked: “But in Hungarian, is it the same word?” He repeated evasively: “It means the same thing!” Undeterred, I pressed him: “But what are the words in Hungarian?” Then, one by one, he enumerated, almost with embarrassment, or at least with a certain reticence, as though there were something immodest about it, the four magic words which I have never forgotten: drágám, kedvesem, aranyoskám, édesem. Fascinated, I relentlessly pestered him, begging him to translate for me what each word meant. Drágám, my darling; kedvesem, my beloved; and two other words whose sensual literalness I would never forget: aranyoskám, my little golden girl; édesem, my sweet. That evening I discovered that words, like trees, had roots whose magic my father had revealed to me: arany, gold; édes, sweet; each of these terms enriched by a lovingly enveloping possessiveness. All of a sudden, the blueprint of my native French glowed from within.

Those four words opened up another world, another language that would one day be born within my own language -- and the conviction that no word that speaks of what is human is untranslatable.

Translation as Transhumance, The Feminist Press at CUNY, 2017.

February 7

One evening is particular stands out in my memory, when for the first time I experienced viscerally, without yet realizing its significance, what ‘translation’ would come to mean for me. It all happened with the utmost simplicity, as is often the case when something is important. He initially translated a word used by his brother or one of his sisters as ‘beloved,’ stumbled over the next word and repeated this -- actually rather ordinary -- adjective once, stumbled again, and then repeated it a second time. That triggered something in me. I dared to interrupt him. I asked: “But in Hungarian, is it the same word?” He repeated evasively: “It means the same thing!” Undeterred, I pressed him: “But what are the words in Hungarian?” Then, one by one, he enumerated, almost with embarrassment, or at least with a certain reticence, as though there were something immodest about it, the four magic words which I have never forgotten: drágám, kedvesem, aranyoskám, édesem. Fascinated, I relentlessly pestered him, begging him to translate for me what each word meant. Drágám, my darling; kedvesem, my beloved; and two other words whose sensual literalness I would never forget: aranyoskám, my little golden girl; édesem, my sweet. That evening I discovered that words, like trees, had roots whose magic my father had revealed to me: arany, gold; édes, sweet; each of these terms enriched by a lovingly enveloping possessiveness. All of a sudden, the blueprint of my native French glowed from within.

Those four words opened up another world, another language that would one day be born within my own language -- and the conviction that no word that speaks of what is human is untranslatable.

Translation as Transhumance, The Feminist Press at CUNY, 2017.

February 7

2023

Hilary Mantel's publicity photograph for the Reith Lecture Series, 2017 - BBC Radio 4

Hilary Mantel's publicity photograph for the Reith Lecture Series, 2017 - BBC Radio 4

On Writing: Wisdom from Hilary Mantel

In 2017, the acclaimed British novelist Hilary Mantel (1952 – 2022) gave that year’s Reith Lectures for the BBC. In a series of five linked and remarkable presentations, she talked about the art of writing historical fiction. Her insights into the writing process are the result of years of honing her craft in a series of formidable novels: Wolf Hall, Bring up the Bodies, Beyond Black, The Mirror and the Light, A Place of Greater Safety.

Here are just three important insights into the process of writing that she included in her lectures:

The raw materials of fiction

“Evidence is always partial. Facts are not truth, though they are part of it – information is not knowledge. And history is not the past - it is the method we have evolved of organizing our ignorance of the past. It’s the record of what’s left on the record. It’s the plan of the positions taken, when we to stop the dance to note them down. It’s what’s left in the sieve when the centuries have run through it – a few stones, scraps of writing, scraps of cloth. It is no more ‘the past’ than a birth certificate is a birth, or a script is a performance, or a map is a journey. It is the multiplication of the evidence of fallible and biased witnesses, combined with incomplete accounts of actions not fully understood by the people who performed them. It’s no more than the best we can do, and often it falls short of that.”

“An event you choose to tell may not be dramatic in itself. Your scene may be as simple as a woman writing a letter, when a man comes in and interrupts her. But when two people are talking in a room, they have a hinterland, and you must suggest it. To that one moment, you bring a sense of every moment that led us there, everything that has brought your woman to this hour, this room, this desk. The multitude of life choices. The motives, conscious or unconscious. The wishes, dreams and desires, all held invisibly within the body whose actions you describe. They hover over the text like guardian angels.”

Writing history/writing fiction

“The task of historical fiction is to take the past out of the archive and relocate it in a body.”

“Landscapes, streetscapes, objects, are dead in themselves. They only come alive through the senses of your character, though his perceptions, his opinions, his point of view. There are no special tricks to make exposition work. There are only different levels of skill, in the author…. You cannot give a complete account. A complete thing is an exhausted thing. You are looking for the one detail that lights up the page: one line, to perturb or challenge the reader, make him feel acknowledged, and yet estranged.”

The hard work of writing

“…you educate yourself towards you characters and that’s why it takes such a long time. That’s what all the hours, days, years in libraries are about. It’s about growing knowledge, knowledge and another sensibility that will stand beside the one you started out with, the one that’s native to you.”

“You don’t know what you’re doing, till you try to do it. As capacity increases, so does ambition. But when it comes getting the words on the page, you can only work breath by breath, line by line.”

“In time I understood one thing: that you don’t become a novelist to become a spinner of entertaining lies: you become a novelist so you can tell the truth.”

These five lectures:

October 19

In 2017, the acclaimed British novelist Hilary Mantel (1952 – 2022) gave that year’s Reith Lectures for the BBC. In a series of five linked and remarkable presentations, she talked about the art of writing historical fiction. Her insights into the writing process are the result of years of honing her craft in a series of formidable novels: Wolf Hall, Bring up the Bodies, Beyond Black, The Mirror and the Light, A Place of Greater Safety.

Here are just three important insights into the process of writing that she included in her lectures:

The raw materials of fiction

“Evidence is always partial. Facts are not truth, though they are part of it – information is not knowledge. And history is not the past - it is the method we have evolved of organizing our ignorance of the past. It’s the record of what’s left on the record. It’s the plan of the positions taken, when we to stop the dance to note them down. It’s what’s left in the sieve when the centuries have run through it – a few stones, scraps of writing, scraps of cloth. It is no more ‘the past’ than a birth certificate is a birth, or a script is a performance, or a map is a journey. It is the multiplication of the evidence of fallible and biased witnesses, combined with incomplete accounts of actions not fully understood by the people who performed them. It’s no more than the best we can do, and often it falls short of that.”

“An event you choose to tell may not be dramatic in itself. Your scene may be as simple as a woman writing a letter, when a man comes in and interrupts her. But when two people are talking in a room, they have a hinterland, and you must suggest it. To that one moment, you bring a sense of every moment that led us there, everything that has brought your woman to this hour, this room, this desk. The multitude of life choices. The motives, conscious or unconscious. The wishes, dreams and desires, all held invisibly within the body whose actions you describe. They hover over the text like guardian angels.”

Writing history/writing fiction

“The task of historical fiction is to take the past out of the archive and relocate it in a body.”

“Landscapes, streetscapes, objects, are dead in themselves. They only come alive through the senses of your character, though his perceptions, his opinions, his point of view. There are no special tricks to make exposition work. There are only different levels of skill, in the author…. You cannot give a complete account. A complete thing is an exhausted thing. You are looking for the one detail that lights up the page: one line, to perturb or challenge the reader, make him feel acknowledged, and yet estranged.”

The hard work of writing

“…you educate yourself towards you characters and that’s why it takes such a long time. That’s what all the hours, days, years in libraries are about. It’s about growing knowledge, knowledge and another sensibility that will stand beside the one you started out with, the one that’s native to you.”

“You don’t know what you’re doing, till you try to do it. As capacity increases, so does ambition. But when it comes getting the words on the page, you can only work breath by breath, line by line.”

“In time I understood one thing: that you don’t become a novelist to become a spinner of entertaining lies: you become a novelist so you can tell the truth.”

These five lectures:

- The Day is for the Living

- The Iron Maiden

- Silence Grips the Town

- Can These Bones Live?

- Adaptation

October 19

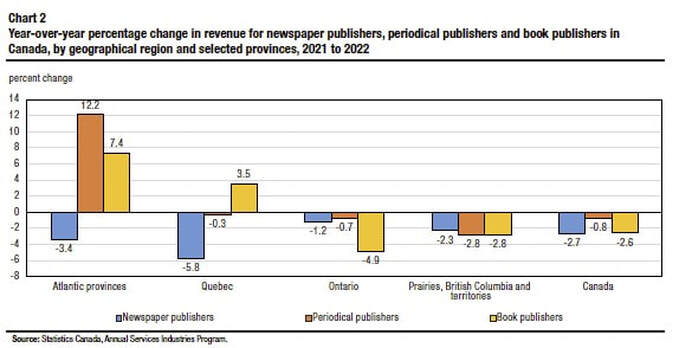

No recovery in sight for publishing industries

A new report by Megan McMaster from Statistics Canada has a mix of good and bad news for Canada’s cultural sector.

First the good news: “Nationally, there was strong revenue and salary growth in 2022 across most of the industries, except the publishing industries, which continued to see declining revenues. The strongest revenue growth was seen in the promoters (presenters) of performing arts, sports and similar events industry group (+145.8%), while the largest decline was in newspaper publishers (-2.7%).”

And then the bad news: “No recovery in sight for publishing industries. The newspaper, book and periodical publishing industries did not experience the same post-pandemic bounce back in 2022 as the rest of the culture, arts, entertainment and recreation industries, with revenues contracting across all three industries. The publishing industries continued to face challenges in 2022, including the rising cost of paper, competition for readers and advertising dollars, and pressures to operate in a more digital environment. Of these publishing industries, the largest revenue decline was observed in newspaper publishers (-2.7%), followed by book publishers (-2.6%) and periodical publishers (-0.8%).

Across Canada, only two regions (Quebec and the Atlantic provinces) saw revenue growth in these industries (see Chart 2). Book publishers in Quebec had modest revenue growth of 3.5% in 2022, while revenue declines were observed in the other publishing industries, with newspaper publishers down 5.8% and periodical publishers relatively flat (-0.3%). In the Atlantic region, the revenues of periodical publishers (+12.2%) and book publishers (+7.4%) grew in 2022, but not for newspaper publishers (3.4%).”

“Return to life after two years of the COVID-19 pandemic: A look at culture, arts, entertainment and recreation services in 2022.”

Release date: August 22, 2023

September 4

A new report by Megan McMaster from Statistics Canada has a mix of good and bad news for Canada’s cultural sector.

First the good news: “Nationally, there was strong revenue and salary growth in 2022 across most of the industries, except the publishing industries, which continued to see declining revenues. The strongest revenue growth was seen in the promoters (presenters) of performing arts, sports and similar events industry group (+145.8%), while the largest decline was in newspaper publishers (-2.7%).”

And then the bad news: “No recovery in sight for publishing industries. The newspaper, book and periodical publishing industries did not experience the same post-pandemic bounce back in 2022 as the rest of the culture, arts, entertainment and recreation industries, with revenues contracting across all three industries. The publishing industries continued to face challenges in 2022, including the rising cost of paper, competition for readers and advertising dollars, and pressures to operate in a more digital environment. Of these publishing industries, the largest revenue decline was observed in newspaper publishers (-2.7%), followed by book publishers (-2.6%) and periodical publishers (-0.8%).

Across Canada, only two regions (Quebec and the Atlantic provinces) saw revenue growth in these industries (see Chart 2). Book publishers in Quebec had modest revenue growth of 3.5% in 2022, while revenue declines were observed in the other publishing industries, with newspaper publishers down 5.8% and periodical publishers relatively flat (-0.3%). In the Atlantic region, the revenues of periodical publishers (+12.2%) and book publishers (+7.4%) grew in 2022, but not for newspaper publishers (3.4%).”

“Return to life after two years of the COVID-19 pandemic: A look at culture, arts, entertainment and recreation services in 2022.”

Release date: August 22, 2023

September 4

photo by Michelle Valberg - https://www.charlottegray.ca

photo by Michelle Valberg - https://www.charlottegray.ca

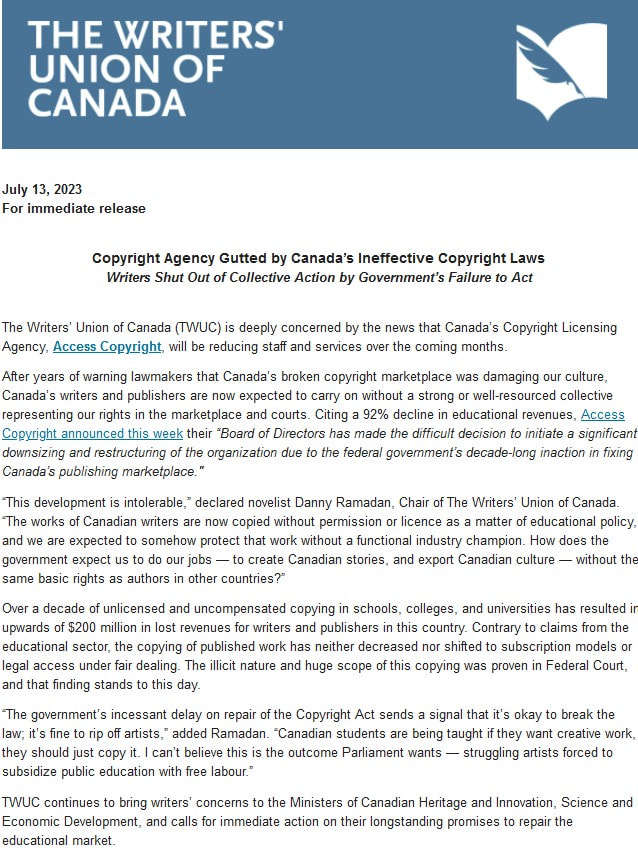

Serious Trouble for Canadian Non-fiction Writing and Publishing

Writing in The Globe and Mail, acclaimed historian Charlotte Gray outlines a dangerous situation for authors of non-fiction.

"[Forty years ago] A non-fiction writer could cover research costs and make a decent living from a combination of publishers’ advances, grants from federal and local arts councils and spinoff articles.

Today, in the words of author and lawyer Mark Bourrie, “it’s horrible out there.” Bourrie has written several well-received books on Canadian history, including the Charles Taylor Prize winner Bush Runner: The Adventures of Pierre-Esprit Radisson, which required months of intense research in libraries and archives plus travel to significant sites. He would like to write more. “But I can only support myself because I practise law.”

…History is just one category within the larger genre of deeply researched non-fiction that struggles to survive in Canada today. Other types of non-fiction by Canadian writers that require several years of research, including popular science, climatology, biography, business writing and essays, are slowly disappearing from bookstores. These days, our publishers’ non-fiction lists are dominated by personal memoirs – books that may be well-written and illuminating, but rarely involve archives, research trips or fact-checking.

…Part of the reason is the precipitous decline of our publishing industry. In the 1980s, there was a healthy publishing ecosystem, with several sturdy Canadian publishers plus a readership eager to buy its products

…Today, most of those Canadian publishers have either closed or been swallowed by the multinational publisher Random House (now Penguin Random House.)

...What can halt this gradual slide into homegrown ignorance about Canadian politics, scientific achievements and history? Granting councils can reconsider the damage to non-fiction writers who want to explore this country’s culture in depth. …The federal government can offer more protections, through subsidies and regulations, for Canadian independent publishers. Provincial education departments can kindle an interest in this country by building more time for Canadian content into their curricula. Without such interventions, argues Bourrie, “we’ll soon be culturally integrated with the United States, and we’ll have lost our own history.”

Excerpted from "The slow, painful demise of Canadian Fiction" by Charlotte Gray,

published in the The Globe and Mail, August 12, 2023

Writing in The Globe and Mail, acclaimed historian Charlotte Gray outlines a dangerous situation for authors of non-fiction.

"[Forty years ago] A non-fiction writer could cover research costs and make a decent living from a combination of publishers’ advances, grants from federal and local arts councils and spinoff articles.

Today, in the words of author and lawyer Mark Bourrie, “it’s horrible out there.” Bourrie has written several well-received books on Canadian history, including the Charles Taylor Prize winner Bush Runner: The Adventures of Pierre-Esprit Radisson, which required months of intense research in libraries and archives plus travel to significant sites. He would like to write more. “But I can only support myself because I practise law.”

…History is just one category within the larger genre of deeply researched non-fiction that struggles to survive in Canada today. Other types of non-fiction by Canadian writers that require several years of research, including popular science, climatology, biography, business writing and essays, are slowly disappearing from bookstores. These days, our publishers’ non-fiction lists are dominated by personal memoirs – books that may be well-written and illuminating, but rarely involve archives, research trips or fact-checking.

…Part of the reason is the precipitous decline of our publishing industry. In the 1980s, there was a healthy publishing ecosystem, with several sturdy Canadian publishers plus a readership eager to buy its products

…Today, most of those Canadian publishers have either closed or been swallowed by the multinational publisher Random House (now Penguin Random House.)

...What can halt this gradual slide into homegrown ignorance about Canadian politics, scientific achievements and history? Granting councils can reconsider the damage to non-fiction writers who want to explore this country’s culture in depth. …The federal government can offer more protections, through subsidies and regulations, for Canadian independent publishers. Provincial education departments can kindle an interest in this country by building more time for Canadian content into their curricula. Without such interventions, argues Bourrie, “we’ll soon be culturally integrated with the United States, and we’ll have lost our own history.”

Excerpted from "The slow, painful demise of Canadian Fiction" by Charlotte Gray,

published in the The Globe and Mail, August 12, 2023

And then there are financial setbacks for writers:

|

People and their Books: Sarah Bakewell # 2 – Anton Chekhov (1860 -1904) and Vasily Grossman (1905- 1964)

In her book, Humanly Possible – Seven Hundred Years of Humanist Freethinking, Inquiry, and Hope, former library curator and now acclaimed author, Sarah Bakewell, presents a series of vignettes about the relationship people have with books. In this excerpt, Bakewell links the Russian short-story writer and playwright, Anton Chekhov, with the Ukrainian chemical engineer and creative writer, Vasily Grossman. “[Chekhov’s] short stories, especially, are humanistic in the close attention they pay to events (or quiet non-events) from people’s everyday lives: moments of love or heartbreak, journeys, deaths, boring days. His views on religion and morality were also those of a humanistic: he disliked dogma and was skeptical about supernatural beliefs. As one twentieth-century admirer of Chekhov wrote: He said – and no on had said this before, not even Tolstoy – that first and foremost we are all of us human beings. Do you understand? Human beings! He said something no one in Russia had ever said. He said that first of all we are human beings – and only secondly are be bishops, Russians, shopkeepers, Tartars, workers …Chekhov said: let’s put God – and all these grand progressive ideas – to one side. Let’s begin with man; let’s be kind and attentive too the individual man. These words area actually spoken by a fictional character, in a scene from the novel Life and Fat by the Jewish Ukrainian writer, Vasily Grossman…Like Chekhov, Grossman was a scientist as well as a creative writer: he began in a career as a chemical engineer. Then he took up fiction, much of it light and comic at first. And journalism during the Second World War, especially by filing reports from the battle front in Stalingrad. In the 1950s he worked on Life and Fate…. [The novel] plunges us into the very worst that the twentieth century had to offer: war, mass murder, cold, hunger, betrayal, racist persecution in both Nazi-occupied territory and the Soviet Union – in short, human grief and suffering on a staggering scale. … But through all of this, Grossman imbues the narrative with his humanistic sensibility, putting individuals at the centre, never ideas or ideals.” Bakewell then outline’s Grossman’s difficult and often perilous journey in getting his book into print: “It was immediately hailed as a twentieth-century masterwork, comparable to Tolstoy’s War and Peace, or to an interlinked series of Chekhov stories. Part of its fascination was its own story; one of survival against the odds. Like so many works by our humanists in earlier times, it had been saved by ingenuity, concealment, rescue, and reduplication. And as Petrarch and Bocaccio and the early humanist printers knew, nothing is so good for rescuing a book as making lots of copies of it.” Sarah Bakewell, Humanly Possible – Seven Hundred Years of Humanist Freethinking, Inquiry, and Hope, Alfred Knopf Canada / Penguin Random House, 2023, pp. 360-2 June 24 |

People and their Books: Sarah Bakewell #1 - Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592)

In her book Humanly Possible – Seven Hundred Years of Humanist Freethinking, Inquiry, and Hope, former library curator and now acclaimed author, Sarah Bakewell, presents a series of vignettes about the relationship people have with books.

Here she presents the example of French essayist Michel de Montaigne:

“Michel did know his classics intimately, and his love for his favourite authors was profound. He built up his own book collection and housed them on shelves built to fit the round interior of his tower. He also had that tower’s ceiling beams painted with quotations, so that he could look up and see them at any time…In pride of place was Terrence’s Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto: “I am human, and consider nothing human alien to me.” …

Yet Montaigne trashes all the humanistic pieties on the subject of reading. As soon as he gets bored with a book, he says he flings it aside…

Instead, he likes books when they enhance life and when they expand his understanding of the many people who have lived in the past. Biographies and histories are good, because they show the human being “more alive and entire than in any other place – the diversity and truth of his inner qualities in the mass and in the detail, the variety of ways he is put together, and the accidents that threaten him.”

Of his own work, Sarah Bakewell adds:

“the Essays return constantly to the classic humanistic themes of moral judgment, courtesy, education, virtue, politics, elegant writing, rhetoric, the beauties of books and texts, and the question of whether we are excellent or despicable. But, pondering each of these themes with a skeptical and questioning eye, he dismantles them. Once they are lying around him in pieces, he reassembles them in a more interesting, more disconcerting, and more thought-provoking spirit than before.”

Sarah Bakewell, Humanly Possible – Seven Hundred Years of Humanist Freethinking, Inquiry, and Hope, Alfred Knopf Canada /Penguin Random House, 2023, pp. 157-8.

June 20

In her book Humanly Possible – Seven Hundred Years of Humanist Freethinking, Inquiry, and Hope, former library curator and now acclaimed author, Sarah Bakewell, presents a series of vignettes about the relationship people have with books.

Here she presents the example of French essayist Michel de Montaigne:

“Michel did know his classics intimately, and his love for his favourite authors was profound. He built up his own book collection and housed them on shelves built to fit the round interior of his tower. He also had that tower’s ceiling beams painted with quotations, so that he could look up and see them at any time…In pride of place was Terrence’s Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto: “I am human, and consider nothing human alien to me.” …

Yet Montaigne trashes all the humanistic pieties on the subject of reading. As soon as he gets bored with a book, he says he flings it aside…

Instead, he likes books when they enhance life and when they expand his understanding of the many people who have lived in the past. Biographies and histories are good, because they show the human being “more alive and entire than in any other place – the diversity and truth of his inner qualities in the mass and in the detail, the variety of ways he is put together, and the accidents that threaten him.”

Of his own work, Sarah Bakewell adds:

“the Essays return constantly to the classic humanistic themes of moral judgment, courtesy, education, virtue, politics, elegant writing, rhetoric, the beauties of books and texts, and the question of whether we are excellent or despicable. But, pondering each of these themes with a skeptical and questioning eye, he dismantles them. Once they are lying around him in pieces, he reassembles them in a more interesting, more disconcerting, and more thought-provoking spirit than before.”

Sarah Bakewell, Humanly Possible – Seven Hundred Years of Humanist Freethinking, Inquiry, and Hope, Alfred Knopf Canada /Penguin Random House, 2023, pp. 157-8.

June 20

How This Leads to That: Joining the Dots After a Time of Plague,

In his monumental work The Earth Transformed - An Untold Story, Oxford University’s global historian, Peter Frankopan joins the dots between some remarkable post-pandemic events in history. This one links the Black Death with autoimmune diseases, a shortage of scribes, and the invention of the printing press.

"…many of those who survived the plague may have done so because they were carrying a genetic mutation that served to offer a layer of protection to the immune system. Ironically, this mutation, known as ERAP2, is now associated with several autoimmune disorders, such as Crohn ‘s disease, lupus, and rheumatoid arthritis: in other words, alleles that protected against Black Death confer raised risk for diseases for people alive today.

…The aftermath of plague also saw new fashions, diets and attitudes toward luxury goods, partly as a result of the emergence of competitive consumption, partly because smaller populations meant goods cost less, and partly because of the euphoria of having dodged death’s call. Protein availability not only soared in Europe because there were fewer people to feed, but as farmers and herders were forced to find new markets for their livestock – opening up what one historian has called an international meat trade. It has been argues too that the deaths of so many copyists during the pandemic led to the fall of the price of paper −something that spurred literacy levels and perhaps even helped prompt the print revolution of Johannes Gutenberg and others."

Peter Frankopan: The Earth Transformed – An Untold History, Alfred Knopf, 2003, p. 313-4

June 4

In his monumental work The Earth Transformed - An Untold Story, Oxford University’s global historian, Peter Frankopan joins the dots between some remarkable post-pandemic events in history. This one links the Black Death with autoimmune diseases, a shortage of scribes, and the invention of the printing press.

"…many of those who survived the plague may have done so because they were carrying a genetic mutation that served to offer a layer of protection to the immune system. Ironically, this mutation, known as ERAP2, is now associated with several autoimmune disorders, such as Crohn ‘s disease, lupus, and rheumatoid arthritis: in other words, alleles that protected against Black Death confer raised risk for diseases for people alive today.

…The aftermath of plague also saw new fashions, diets and attitudes toward luxury goods, partly as a result of the emergence of competitive consumption, partly because smaller populations meant goods cost less, and partly because of the euphoria of having dodged death’s call. Protein availability not only soared in Europe because there were fewer people to feed, but as farmers and herders were forced to find new markets for their livestock – opening up what one historian has called an international meat trade. It has been argues too that the deaths of so many copyists during the pandemic led to the fall of the price of paper −something that spurred literacy levels and perhaps even helped prompt the print revolution of Johannes Gutenberg and others."

Peter Frankopan: The Earth Transformed – An Untold History, Alfred Knopf, 2003, p. 313-4

June 4

The Politics of Printing: Thomas Newcomb and Marchemont Nedham

Last week, as the Coronation events concluded, my thoughts turned to that convulsive time in British history when there was no monarch. In 1649, King Charles I was tried and executed for treason and “the most extraordinary and experimental decade in Britain’s history” began when “a conservative people tried a revolution.”

Marchemont Nedham was at the centre, looking for ways to control public information. At a time when newspapers had not yet been invented, he was “the irrepressible newspaperman and puppet master of propaganda.” In the years before writing Paradise Lost, John Milton also vetted material to ensure it was correctly supportive of the new crownless order of government. This was a new form of mass communication: broadsheets and newspapers, designed to spread official and often not-so-official versions of the truth. Did the execution of the king also mean the end of the monarchy? The country was divided; the members of the Commonwealth government were worried.

In her fascinating portrait of this tense and turbulent political decade, British historian Ann Keay includes a vignette about the printing process in the late seventeenth century, the production and distribution network that Marchemont Nedham relied on. In his pressroom on Thames Street in London, the printer Thomas Newcomb has just received the latest edition of Mercurius Politicus, from Marchemont Nedham, the author and publisher. This is what he does with it:

“In the age of the hand printing press the business of producing weekly over a thousand issues of a sixteen-page publication was a demanding physical operation. Each pair of pages of type, locked into place in an iron frame, was placed, face-up, on a block of stone set into a sliding carriage. The pressmen applied on to the upturned letters by dabbing them with a soft leather inking ball. A wooden frame containing a large sheet of paper was then lowered onto the letters and this whole assemblage slid on wooden rails into the press itself. By means of a handle, the pressmen lowered a block of perfectly flat wood or stone known as the ‘platen’ onto the paper from above, so pressing it down onto the inked letters. Raising the platen and drawing the carriage back, they opened the frame, and peeled the freshly printed paper off the metal type. This was handed over to their colleagues who draped each one over the latticework of wooden rails suspended from the printing house ceiling.

The pressmen worked into the night heaving down the platen, drawing the carriage back and forth, peeling off page after page, and replacing the paper and ink with each impression. The room rang with the creak and clatter of the press, governed by the rhythmic movements of the pressmen, who like oarsmen, kept ‘a constant and methodical posture and gesture in every action of pulling and beating which in a train of work becomes habitual.’ By Thursday morning they had finished. Thousands of dry pages hung from the rails, and the air was thick with the caustic tang of the hot lye into which the ink-clogged letters were plunged for cleaning. By now the work of cutting, compiling and folding the sheets into individual issues was well underway. From Thames Street the completed copies of Politicus were carried forth.”

Anna Keay, The Restless Republic: Britain Without a Crown (William Collins, 2022), p. 133-4.

May 11

Last week, as the Coronation events concluded, my thoughts turned to that convulsive time in British history when there was no monarch. In 1649, King Charles I was tried and executed for treason and “the most extraordinary and experimental decade in Britain’s history” began when “a conservative people tried a revolution.”

Marchemont Nedham was at the centre, looking for ways to control public information. At a time when newspapers had not yet been invented, he was “the irrepressible newspaperman and puppet master of propaganda.” In the years before writing Paradise Lost, John Milton also vetted material to ensure it was correctly supportive of the new crownless order of government. This was a new form of mass communication: broadsheets and newspapers, designed to spread official and often not-so-official versions of the truth. Did the execution of the king also mean the end of the monarchy? The country was divided; the members of the Commonwealth government were worried.

In her fascinating portrait of this tense and turbulent political decade, British historian Ann Keay includes a vignette about the printing process in the late seventeenth century, the production and distribution network that Marchemont Nedham relied on. In his pressroom on Thames Street in London, the printer Thomas Newcomb has just received the latest edition of Mercurius Politicus, from Marchemont Nedham, the author and publisher. This is what he does with it:

“In the age of the hand printing press the business of producing weekly over a thousand issues of a sixteen-page publication was a demanding physical operation. Each pair of pages of type, locked into place in an iron frame, was placed, face-up, on a block of stone set into a sliding carriage. The pressmen applied on to the upturned letters by dabbing them with a soft leather inking ball. A wooden frame containing a large sheet of paper was then lowered onto the letters and this whole assemblage slid on wooden rails into the press itself. By means of a handle, the pressmen lowered a block of perfectly flat wood or stone known as the ‘platen’ onto the paper from above, so pressing it down onto the inked letters. Raising the platen and drawing the carriage back, they opened the frame, and peeled the freshly printed paper off the metal type. This was handed over to their colleagues who draped each one over the latticework of wooden rails suspended from the printing house ceiling.

The pressmen worked into the night heaving down the platen, drawing the carriage back and forth, peeling off page after page, and replacing the paper and ink with each impression. The room rang with the creak and clatter of the press, governed by the rhythmic movements of the pressmen, who like oarsmen, kept ‘a constant and methodical posture and gesture in every action of pulling and beating which in a train of work becomes habitual.’ By Thursday morning they had finished. Thousands of dry pages hung from the rails, and the air was thick with the caustic tang of the hot lye into which the ink-clogged letters were plunged for cleaning. By now the work of cutting, compiling and folding the sheets into individual issues was well underway. From Thames Street the completed copies of Politicus were carried forth.”

Anna Keay, The Restless Republic: Britain Without a Crown (William Collins, 2022), p. 133-4.

May 11

Writing with purpose: to upend established order and upset hierarchies

"…my commitment to writing … does not consist of writing ‘for’ a category of readers, but in writing ‘from’ my experience as a woman and an immigrant of the interior; and from my longer and longer memory of the years I have lived, and from the present, an endless provider of the images and words of others. This commitment through which I pledge myself in writing is supported by the belief, which has become a certainty, that a book can contribute to change in private life, help to shatter the loneliness of experiences endured and repressed, and enable beings to reimagine themselves. When the unspeakable is brought to light, it is political.

…In the bringing to light of the social unspeakable, of those internalized power relations linked to class and/or race, and gender too, felt only by the people who directly experience their impact, the possibility of individual but also collective emancipation emerges. To decipher the real world by stripping it of the visions and values that language, all language, carries within it is to upend its established order, upset its hierarchies."

Annie Ernaux, from her Nobel Prize Lecture in Stockholm, December, 2022.

Each Nobel prize has a “motivation” and in Annie Ernaux’s case, it was awarded “for the courage and clinical acuity with which she uncovers the roots, estrangements and collective restraints of personal memory.”

Illustration by Niklas Elmehed - Nobel Prize Outreach

April 28

"…my commitment to writing … does not consist of writing ‘for’ a category of readers, but in writing ‘from’ my experience as a woman and an immigrant of the interior; and from my longer and longer memory of the years I have lived, and from the present, an endless provider of the images and words of others. This commitment through which I pledge myself in writing is supported by the belief, which has become a certainty, that a book can contribute to change in private life, help to shatter the loneliness of experiences endured and repressed, and enable beings to reimagine themselves. When the unspeakable is brought to light, it is political.

…In the bringing to light of the social unspeakable, of those internalized power relations linked to class and/or race, and gender too, felt only by the people who directly experience their impact, the possibility of individual but also collective emancipation emerges. To decipher the real world by stripping it of the visions and values that language, all language, carries within it is to upend its established order, upset its hierarchies."

Annie Ernaux, from her Nobel Prize Lecture in Stockholm, December, 2022.

Each Nobel prize has a “motivation” and in Annie Ernaux’s case, it was awarded “for the courage and clinical acuity with which she uncovers the roots, estrangements and collective restraints of personal memory.”

Illustration by Niklas Elmehed - Nobel Prize Outreach

April 28

|

Detail from a Jan van der Straet engraving in the Wellcome Collection: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/gepksmnb

|

Small presses are thriving even as “big” presses try to become ever bigger.

A recent article in the UK celebrated no fewer than 48 successful "small" publishers. Their success is based on “grassroots bookmaking” according to Philip Jones, chair of the The Bookseller’s publishing awards. “These publishers are reaping the rewards from dedicated and often inspirational publishing, hands-on author care and community building.” One of the finalists, Kevin Duffy, of Bluemoose Books in the north of England describes the work as “Tough, every week is a battle … [but] independent bookshops are telling us that readers are saying they’re not finding anything different, and independent bookshops are pointing to smaller independent publishers. I think that’s one of the reasons why independent presses are being shortlisted and winning literary prizes, because we are taking risks the bigger publishers aren’t.” Penny Thomas, of Firefly Press in Wales says that ever-increasing competition for contracts and sales “means sales have to grow fast for indie publishers to survive. Small presses, including those based outside of London, do definitely publish big books, but with relatively diminutive marketing budgets we are always fighting to be seen in the trade and to get those books out to readers…. We are realistic enough to know that we have to stay at the very top of our game and publish outstanding books.” Britain’s Small Press of the Year winner will be announced in May. February 25 |

|

Writing Biography or Autobiography: Is it all a matter of perception?

As Cognitive and Computational Neuroscience professor Anil Seth explains, this is where things get really tricky. How to explain choices, motivations, and unique life-stories? “Every time science has displaced us from the centre of things, it has given back far more in return. The Copernican revolution gave us a universe – one which astronomical discoveries of the last hundred years have expanded far beyond the limits of human imagination. Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection gave us a family, a connection to all other living species and an appreciation of deep time and of the power of evolutionary design. And now the science of consciousness … is breaching the last remaining bastion of human exceptionalism – and presumed specialness of our conscious minds – and showing this, too, to be deeply inscribed into the wider patterns of nature. Everything in conscious experience is a perception of sorts, and every perception is a kind of controlled – or controlling – hallucination. What excites me most about this way of thinking is how far it may take us. Experiences of free will are perceptions. The flow of time is a perception. Perhaps even the three-dimensional structure of our experienced world and the sense that the contents of perceptual experience are objectively real – these may be aspects of perception too.” From: Being You – A New Science of Consciousness by Anil Seth, Dutton/Penguin Random House, 2021, p.282 February 11 |

Writer and Editor – Poetry

Speaking in an interview of two editors that she has worked with, Evelyn Lau explains the creative input she values:

"…both have been really good about making extremely minor adjustment, down to, as I say, a punctuation mark; that might be the only thing that they would suggest changing in a poem. But, of course, by the time the manuscript has landed on their desk, I’ve gone through it so many times that I don’t want huge intervention. That would be just horrible. But they’ve both been really sensitive about, just making really slight but important suggestions where, one thing that changed in a poem can really change the entire poem. So I am looking for somebody with that sort of eye, that is very close and not ham-handed at all. I guess that would be the term, right? As a poet you don’t want someone coming in and misunderstanding what you do. But even prose editors can misunderstand, especially if your prose is poetic and at the forefront of their thoughts is something like, is the grammar correct? [Laughs.] Well it may not be entirely correct, but once you correct the grammar, it completely throws off the rhythm. So you want someone who can understand the artistry that you are trying to do."

From: John Vardon In Conversation - The Constant Clamour for Words: A Conversation with Evelyn Lau. The New Quarterly – Canadian Writers & Writing, Number 165, Winter 2003, p. 41.

www.tnq.ca

February 6

Speaking in an interview of two editors that she has worked with, Evelyn Lau explains the creative input she values:

"…both have been really good about making extremely minor adjustment, down to, as I say, a punctuation mark; that might be the only thing that they would suggest changing in a poem. But, of course, by the time the manuscript has landed on their desk, I’ve gone through it so many times that I don’t want huge intervention. That would be just horrible. But they’ve both been really sensitive about, just making really slight but important suggestions where, one thing that changed in a poem can really change the entire poem. So I am looking for somebody with that sort of eye, that is very close and not ham-handed at all. I guess that would be the term, right? As a poet you don’t want someone coming in and misunderstanding what you do. But even prose editors can misunderstand, especially if your prose is poetic and at the forefront of their thoughts is something like, is the grammar correct? [Laughs.] Well it may not be entirely correct, but once you correct the grammar, it completely throws off the rhythm. So you want someone who can understand the artistry that you are trying to do."

From: John Vardon In Conversation - The Constant Clamour for Words: A Conversation with Evelyn Lau. The New Quarterly – Canadian Writers & Writing, Number 165, Winter 2003, p. 41.

www.tnq.ca

February 6

|

“The hand speaks to the brain as surely as the brain speaks to the hand.”

Robertson Davies, What’s Bred in the Bone In a Guardian article on British novelist Alex Preston, who’s composing his next novel entirely in longhand, the interviewer himself says that using a pen and notebook keeps him in touch with the craft of writing. “It’s a deep-felt, uninterrupted connection between thought and language which technology seems to short circuit.” Canadian journalist, Andrew Coyne agrees: “Text on a computer is definitely corrigible: We commit to nothing, either in words or sentence structure…Handwriting, to the contrary, forces us to make an investment. It inclines us thus to compose the sentence in our heads first – and the other sort of sentence you can compose and keep in your head is likely to be shorter and clearer than otherwise.” Military historian Nathan Greenfield says part of the joy of using a fountain pen is that it’s a beautiful object, but also that it gives him a feel for language. …With a pen and ink you’re your own software. And, an added bonus, there’s no metadata; no one tracks your notebooks.” Ted Bishop: The Social Life of Ink - Culture, Wonder, and Our Relationship with the Written Word, Viking/Penguin, 2014, p. 298-9. January 29 |

|

Thinking about editing and corrections and lots of paper

“The printing process involves more than just reformatting a manuscript with the goal of generating a large number of copies to circulate through time and space. It also encompasses a text’s transition into a sphere of error correction and heightened claims to truth. Printing involves press proofs, preliminary corrections, and thorough reviews. The inevitability of printing errors is not eliminated by the ability to print an improved, revised edition of a book, but it is kept in check. … Modern authors are their own editors even before they approve their manuscripts for publication. When Erasmus of Rotterdam described the printed book as an object that permitted, and demanded, a theoretically endless sequence of corrections and revisions, he was not referring to printing alone. Correcting misprints is the job of the printer and typesetter, but factual errors or imperfect verses are corrected in the manuscript itself. In other words, this is the job of the author. In a letter from 1651, Guez de Balzac wrote that in the course of abridging, editing, and reworking a single satire he has used up ‘une demy rame de papier,’ or half a ream. Taken literally, this would have been 250 sheets of paper.” Lothar Müller: White Magic – The Age of Paper, translated by Jessica Spengler, Polity Press, 2014. January 24 |

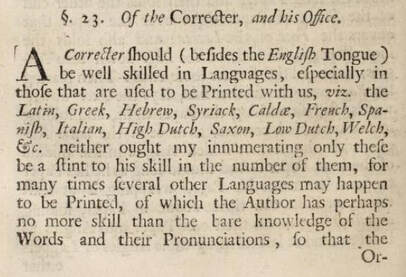

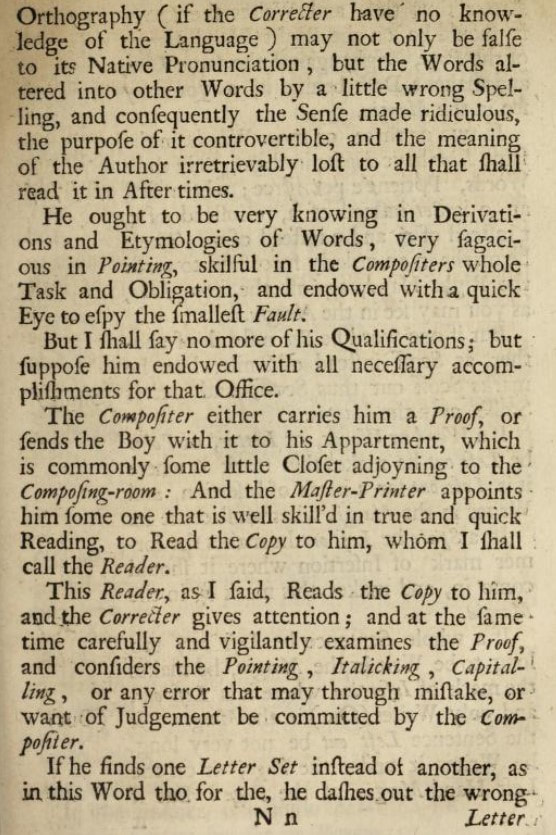

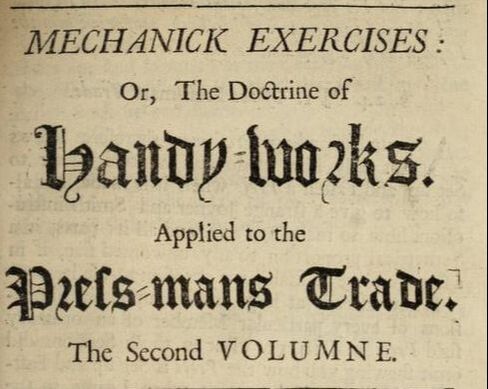

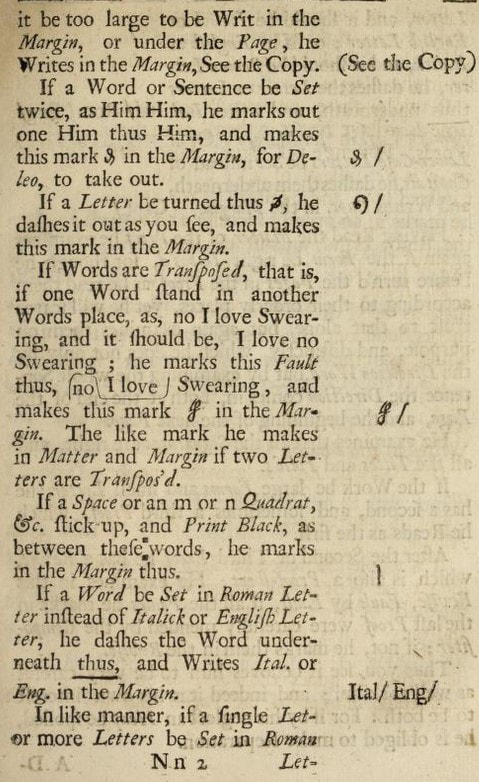

From the Office of Correction: A Guide to Proofing from the 17th Century

In 1677 in England, Jospeh Moxon (1627 - 1691) published a how-to guide for printers. Here are the pages from his Mechanik Exercsies, Or The Doctrine of Handy-Works in which he explains how a printer needs to "proof" a page before the final printing stage. He reminds would-be printers/editors that they are financially responsible for errors: "For if by neglect a Heap is spoiled, he is obliged to make Reparation."

To browse this remarkably detailed how-to guide to printing, here is a link to its page on the Internet Archive:

https://archive.org/details/mechanickexercis00moxo/

January 13

In 1677 in England, Jospeh Moxon (1627 - 1691) published a how-to guide for printers. Here are the pages from his Mechanik Exercsies, Or The Doctrine of Handy-Works in which he explains how a printer needs to "proof" a page before the final printing stage. He reminds would-be printers/editors that they are financially responsible for errors: "For if by neglect a Heap is spoiled, he is obliged to make Reparation."

To browse this remarkably detailed how-to guide to printing, here is a link to its page on the Internet Archive:

https://archive.org/details/mechanickexercis00moxo/

January 13

Craft: Editing

"I always wanted to be unseen and unheard, which is what editors should be."

In an interview with National Public Radio's Terry Gross, the American editor Robert Gottlieb stresses "service" as the central role of the editor. Famous for editing works by John le Carré, Joseph Heller, and Toni Morrison, he said, "I feel as an editor, it's my job to make the case that I need to make and then it's his job to eventually agree or disagree. You know, I never cease explaining or telling young people who want to be editors, it's a service job. Our job is to serve the word, serve the author, serve the text. It's not our book, it's not my book. It's his book or her book. But it's a very gratifying job. And I love the editing process. I love it as an editor. And since I've done a lot of writing myself, to my astonishment, I love being edited because it's the process that I like. I don't care whether I'm the editor or the editee. It's fun and it's interesting to see how you can make something that you believe is good even better."

Here's a link to the NPR's Fresh Air interview: https://www.npr.org/2023/01/03/1146641641/robert-gottlieb-caro-power-broker-turn-every-page-lizzie-gottlieb

January 8

"I always wanted to be unseen and unheard, which is what editors should be."

In an interview with National Public Radio's Terry Gross, the American editor Robert Gottlieb stresses "service" as the central role of the editor. Famous for editing works by John le Carré, Joseph Heller, and Toni Morrison, he said, "I feel as an editor, it's my job to make the case that I need to make and then it's his job to eventually agree or disagree. You know, I never cease explaining or telling young people who want to be editors, it's a service job. Our job is to serve the word, serve the author, serve the text. It's not our book, it's not my book. It's his book or her book. But it's a very gratifying job. And I love the editing process. I love it as an editor. And since I've done a lot of writing myself, to my astonishment, I love being edited because it's the process that I like. I don't care whether I'm the editor or the editee. It's fun and it's interesting to see how you can make something that you believe is good even better."

Here's a link to the NPR's Fresh Air interview: https://www.npr.org/2023/01/03/1146641641/robert-gottlieb-caro-power-broker-turn-every-page-lizzie-gottlieb

January 8

Craft: Anne Campbell on Writing

The Deck God

I sit on my deck today

circling in on God

from behind my studio watch grass reach up; shoots

rest on one another leaning forward they bend

in places where elk nest lay their great goodies down

today

beginning is

full of cloud but warmed beyond hope touched

by this gift my soul is making (concrete) words whole

(#8: Banff Poems in Soul to Touch, Hagios Press, Regina, 2009, p.66.)

Anne Campbell (1938 - 2022), writer and long-time arts and

cultural heritage advocate passed away peacefully on October 20th, 2022,

(January 7) in the Palliative Care Unit, Pasqua Hospital, Regina.

The Deck God

I sit on my deck today

circling in on God

from behind my studio watch grass reach up; shoots

rest on one another leaning forward they bend

in places where elk nest lay their great goodies down

today

beginning is

full of cloud but warmed beyond hope touched

by this gift my soul is making (concrete) words whole

(#8: Banff Poems in Soul to Touch, Hagios Press, Regina, 2009, p.66.)

Anne Campbell (1938 - 2022), writer and long-time arts and

cultural heritage advocate passed away peacefully on October 20th, 2022,

(January 7) in the Palliative Care Unit, Pasqua Hospital, Regina.

|

Craft: Setting the tone before a scene of conflict

"The shadows are lengthening. Across the stripped crests of the elms, beyond the curtain of a row of poplars, white house fronts and blue roofs sparkle in the level light. Hardly anyone is about. Jean can hear the creak of wheels ploughing through the mud of a sunken road, but the cart itself is invisible. Etched upon the horizon, a grey horse and a bay are drawing a plough across a gently undulating expanse of stubble, the soft brown clods rising soundlessley beside the gleaming share. A belated puddle shines amongst the tree-trunks, where, overhead, abandoned nests crouch like big black spiders in their web of leafless boughs. The ploughman has reached the end of the field; slowly he swings his horses round and starts a new furrow. The grey horse, now coming toward Jean, conceals both the plough and the bay horse, and seems to be advancing by itself. The wind drops. The creak of cart-wheels has died away. The dead leaves cease rustling. All is still..." From Jean Barois, the 1913 novel by the 1937 Nobel Prize for Literature recipient, Roger Martin du Gard. First English edition translated by Suart Gilbert and published by the Viking Press in 1949. (p. 77) January 5 |

Winter Shades of White

A new year. A clean white page...

"Under a dark sky walking by the river... all was sad-coloured and the colour caught the eye, red and blue and stones in the river beaches brought out by patches of white-blue snow, that is, snow quite white and dead but yet it seems as if some blue or lilac screen masked it somewhere between it and the eye: I have often noticed it. The swells and hillocks of the river sands and fields were sketched and gilded out by frill upon frill of snow...Where the snow lies as in a field the demasking of white light and silvery shade may be watched indeed till brightness and glare is all lost in a perplexity of shadow and in the whitest of things the senes of white is lost, but at a shorter gaze I see two degrees in it - the darker, facing the sky, and the lighter in the tiny cliffs or scarps where the snow is broken or raised into ridges, these catching the sun perhaps or at all event directly hitting the eye and gilded with an arch brightness, like the sweat in the moist hollow between the the eyebrows and the eyelids on a hot day..."

Gerard Manley Hopkins, Journal entry, Winter, 1872.

The Major Works, Oxford World's Classics, 1986, p. 214.

January 1

A new year. A clean white page...

"Under a dark sky walking by the river... all was sad-coloured and the colour caught the eye, red and blue and stones in the river beaches brought out by patches of white-blue snow, that is, snow quite white and dead but yet it seems as if some blue or lilac screen masked it somewhere between it and the eye: I have often noticed it. The swells and hillocks of the river sands and fields were sketched and gilded out by frill upon frill of snow...Where the snow lies as in a field the demasking of white light and silvery shade may be watched indeed till brightness and glare is all lost in a perplexity of shadow and in the whitest of things the senes of white is lost, but at a shorter gaze I see two degrees in it - the darker, facing the sky, and the lighter in the tiny cliffs or scarps where the snow is broken or raised into ridges, these catching the sun perhaps or at all event directly hitting the eye and gilded with an arch brightness, like the sweat in the moist hollow between the the eyebrows and the eyelids on a hot day..."

Gerard Manley Hopkins, Journal entry, Winter, 1872.

The Major Works, Oxford World's Classics, 1986, p. 214.

January 1